After the discovery of the Inca citadel of Machu Picchu was given to the world, surely many of us have wondered about what the daily life of the Incas in Machu Picchu was like. And certainly to answer this question, we resorted to the different studies carried out by archaeologists and scientists over more than 100 years. Very few objects have been rescued from the Incas in Machu Picchu, which makes it even more difficult to discover the information presented to us by our visitor communities.

Formally, there are a series of authors who infer that the ancient Inca city would have been inhabited by high-ranking castes, who were served by a large number of servants, likewise these servants came from the different ethnic groups of South America.

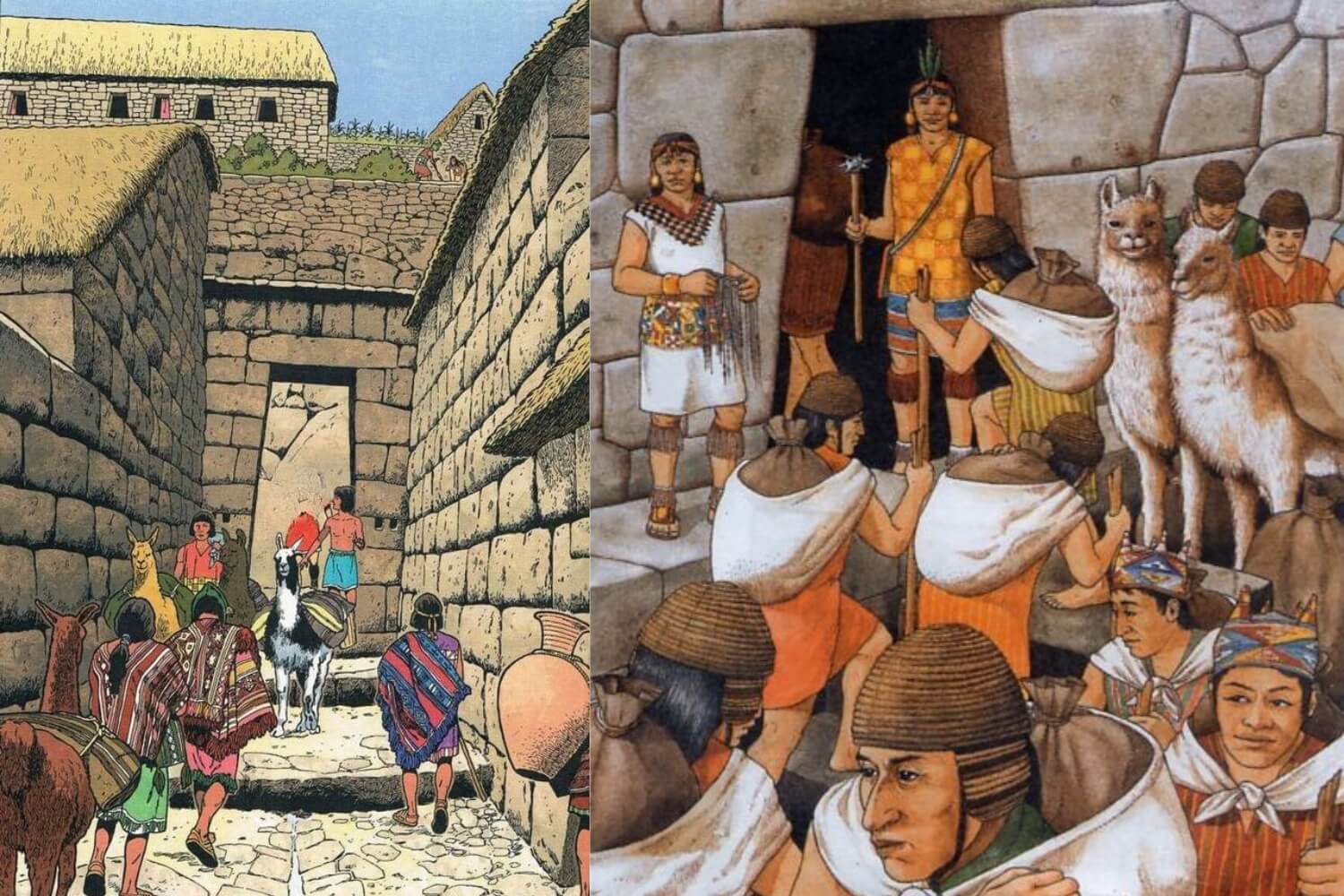

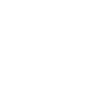

To our knowledge, it was suggested that this place was only dedicated to worship and the spread of religious activities, Machu Picchu was constantly visited by pilgrims from all over the territory of the great Inca empire. These travelers brought their own servants, food, and offerings with them and spent from 1 to more weeks in the Inca palace, possibly seeking to meditate and share their knowledge in the different fields of technology and astronomical sciences, with the Incas of Machu Picchu.

It is known that this sacred place was a center of administrative, religious, and cultural power, run by wise men and philosophers from Tawantinsuyo. Their access to the Inca sanctuary of Machu Picchu was very restricted, only designed for the great leaders of the Incas.

The archaeological site of Machu Picchu corresponds to a royal estate built by Emperor Pachacuteq and controlled by his descendants (or panaca) approximately until the Spanish Conquest. The best-known part of this territory is an architectural complex finely constructed in a graben between the Machu mountains. Picchu and Huayna Picchu to serve as a country palace for the royal family, their guests and servants. Although Bingham referred to it as the “lost city,” probably no more than 750 people lived there at any one time. During the rainy season (November-April), the population probably decreased to only a few hundred people, most of whom were religious specialists and support staff.

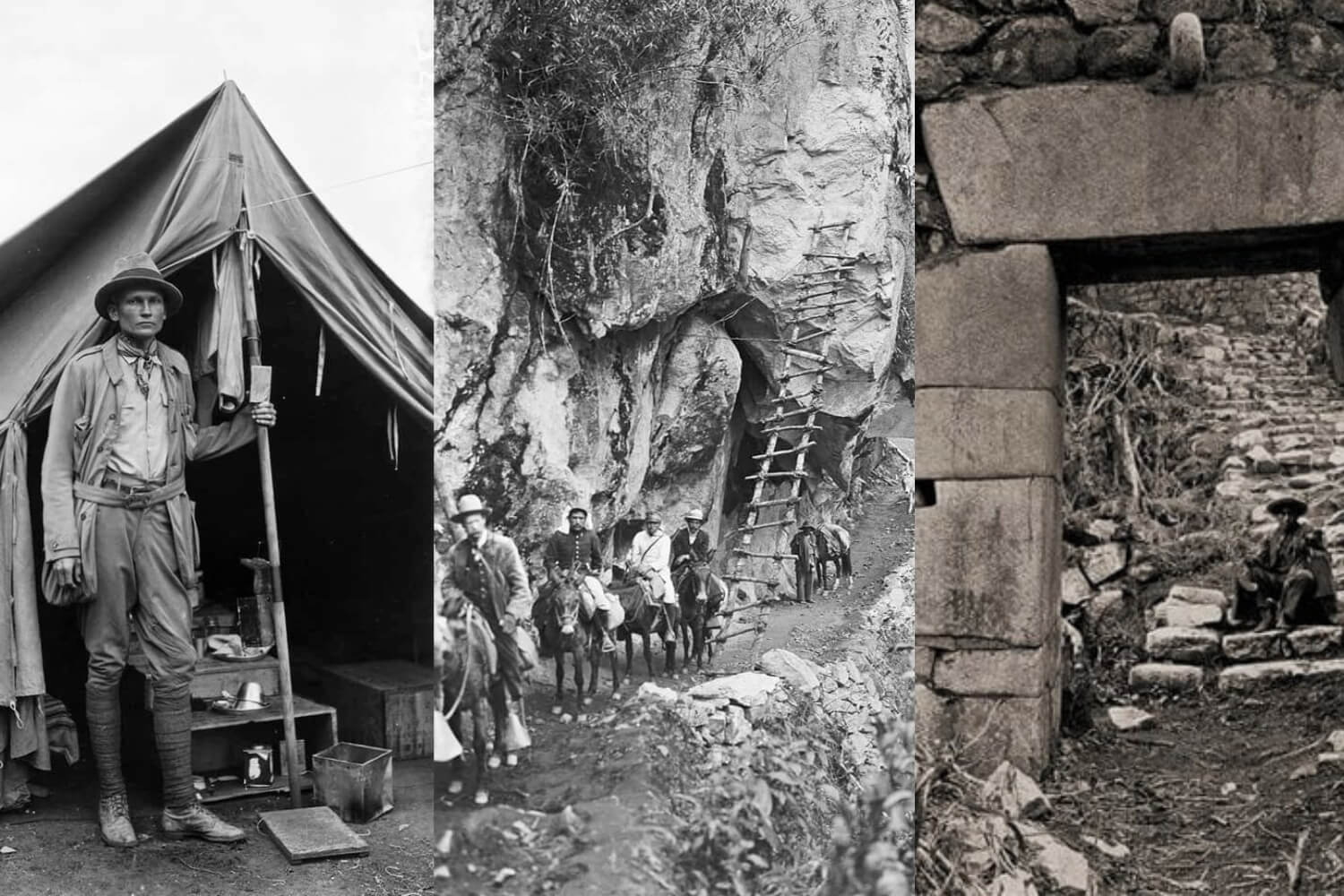

During the Yale Peruvian Expedition of 1912, more than one hundred tombs were found, most of them hidden by the dense cloud forests on the eastern slopes of the site. Concentrated in three groups, the burials were usually placed within crevices beneath large granite outcrops. In many cases, low walls were added to seal these simple tombs and protect them from animals and other intruders. The small number of funerary objects, their modest quality and nature, in addition to the variability of the skeletal remains, indicate that these were the tombs of the servants of Machu Picchu and not burials of members of the royal family or their guests. Subsequent archaeological work at Machu Picchu has failed to discover tombs significantly more elaborate than those found in 1912.

This mortuary pattern is not unexpected, since if members of the Inca elite had died while residing in the country palace, they would have been transported to their main residence in Cusco instead of being buried in Machu Picchu. Because the elite were transported in litters and considering that the trip to the capital took only three days, this option would not have presented serious obstacles. Analysis of the entire osteological collection by John Verano, a physical anthropologist at Tulane University. He concluded that a minimum of 174 individuals were represented in the Machu Picchu osteological sample. Contrary to Eaton’s results, he found that a significant number of these individuals are men.

Furthermore, the presence of children in the Machu Picchu sample, including newborns, and osteological evidence that some of the women had given birth, further undermines Bingham’s Virgins of the Sun hypothesis. When determining the ages of the deceased at Machu Picchu, Verano found a diverse population made up of babies, children, young adults and the elderly. This population was dominated by adults (78% of the skeletons), with at least fourteen individuals that were over fifty years of age, considered old by the standards of the pre-Hispanic world.

The height of the servants of Machu Picchu was short, the men averaged 157.48 cm and the women averaged 149.86 cm. None of the skeletons studied by Verano measured more than 167.64 cm. However, it should be noted that studies of modern Quechua-speaking peoples in the department of Cuzco found that the average height of an adult man was 158.75 cm and that of an adult woman was 144.78 cm. These contemporary farmers in the mountains are remarkably similar in height to those at Machu Picchu some five hundred years ago. Judging by Verano’s findings, the population of Machu Picchu was generally in good health. However, tooth decay was a common problem, suggesting the consumption of high-carbohydrate foods, such as corn. Likewise, in Machu Picchu there are no more severe pathologies, such as skull fractures caused by armed combat. This absence contrasts sharply with finds at other late pre-Hispanic sites in Cuzco.

Similarly, osteological evidence of advanced arthritis and other markers of occupational stress were surprisingly limited. This suggests that the Yanacona workload at Machu Picchu was reasonable, and less than at other types of Inca sites. Although Verano could not confirm Eaton’s claims about the presence of syphilis, he did find evidence of tuberculosis and possible parasitic infections, as he had. However, the servants seem to have generally enjoyed good health. This conclusion was confirmed based on the low frequency of interruptions in the growth of tooth enamel formation. Similarly, the rarity of hypoplasia suggests that the population experienced few serious illnesses during their childhood.

It is reasonable to assume that the good health of the yanaconas of Machu Picchu was based on an adequate diet. Because a limited amount of organic material has survived the heavy rains and temperature fluctuations at Machu Picchu, our understanding of their diet remains limited. However, recent advances in the study of bone chemistry have provided some insights into the products they consumed. Human bone collagen chemistry reflects the foods taken during an individual’s life, but it is often difficult to interpret this data due to the similar results produced by different foods.

The Incas consumed meat and the abundant fragments of animal bones at Inca and pre-Inca sites dispel any doubt about its presence in the diet. Given its location in a cloud forest environment on the eastern slopes of the Andes, what animals were consumed at Machu Picchu? According to Miller’s analysis, the most abundant animal remains found in the funerary caves of Machu Picchu were those of domesticated camelids (llama and alpaca), which represent 88% of the total. When the amount of meat they represent is calculated based on this percentage, camelids make up more than 90% of the remains and Miller believes that more than 95% of the meat consumed in Machu Picchu came from herds of alpacas and llamas.

The natural habitat of both the llama and the alpaca is the high, open grassland, known as puna, at more than 3,800 meters above sea level, and not the densely forested slopes below Machu Picchu between 2,000 and 2,400 meters above sea level. Some patches of high grassland are within a day’s walk of Machu Picchu and it is likely that llamas and alpacas have been driven to these areas and other more distant punas. Domesticated camelids were essential for transport and wool production throughout the Inca Empire and the presence of one or both species will probably have been common near Machu Picchu. Both llamas and alpacas were consumed in Inca times, although their role as a food source is traditionally considered secondary to their other economic functions.

In the case of the Machu Picchu sample, the camelids appear to have been mainly alpacas. Today, the alpaca is prized for its fine wool, in addition to being valued as food. Alpacas generally gather in grasslands above 4,270 meters above sea level, so in Machu Picchu – whose elevation is only 2,440 meters above sea level – alpacas are exotic species brought from another much higher ecozone. Considering that the size of some remains of these camelids is between alpacas and modern llamas. Apparently alpacas and small llamas were brought on foot to Machu Picchu to be sacrificed there and then prepared for funeral ceremonies. In Machu Picchu, more than a millennium later, none of the camelids recovered from the cemeteries were less than two years old and 83% were older than three years. Therefore, at Machu Picchu, old alpacas and llamas appear to have been the meat offered as final food to the deceased yanaconas and their mourners. Perhaps these animals were herded for their wool and made available for slaughter and distribution to servants only when their value as fiber producers had diminished.

The Spanish chronicles of the 16th century leave no doubt that hunting was one of the main activities for the enjoyment of the Inca nobility during their stay in the country palaces. The forested slopes of the mountains surrounding Machu Picchu would have provided an excellent environment for such activities, which has been confirmed by faunal analyses. Furthermore, judging by its remains, the yanaconas buried in Machu Picchu were allowed to consume some wild animals that lived in the dense vegetation of the cloud forest. Among the bones, Bingham’s team recovered evidence of two types of deer (Mazana Americana and Pudu mephistopkeles). Both species are native to the cloud forest. It is significant that there is only one fragment of antler from a white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), an animal that is generally found in archaeological sites on the coast and mountains of Peru; Furthermore, there are no examples of taruka (Hippocamelus antisensis), which inhabits the high areas. Among the remains of Machu Picchu are examples of subtropical paca or agouti (Agouti paca), a culinary delicacy for modern rainforest groups. Additionally, the yanaconas were sometimes able to capture the tasty vizcachas (Ligidium peruanum), animals that still inhabit the rocky outcrops surrounding the ruins of Machu Picchu.

The consumption of these wild animals was occasionally supplemented by opossums (Didelphis albiventris) and subtropical rainforest rodents, such as Abrocoma oblativa, a distant relative of the chinchilla rat (Miller 2003). This evidence suggests that there was a pattern of hunting in the lands surrounding the royal palace. The domesticated guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) was valued by the Incas and their ancestors as a delicacy, probably because its meat and fine flavor provided a pleasant break from the low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet that constituted the daily diet in the Andes. For this reason, guinea pig remains a popular food at festivals in the Peruvian highlands. In Machu Picchu, guinea pig teeth were found in the surroundings of two caves, thus confirming that its meat was consumed as part of funerary rituals.

Judging by Verano’s findings, the population of Machu Picchu was generally in good health. However, tooth decay was a common problem, suggesting the consumption of high-carbohydrate foods, such as corn. It is reasonable to assume that the good health of the yanaconas of Machu Picchu was based on an adequate diet. Because a limited amount of organic material has survived the heavy rains and temperature fluctuations at Machu Picchu, our understanding of their diet remains limited. However, recent advances in the study of bone chemistry have provided some insights into the products they consumed. Human bone collagen chemistry reflects the foods taken during an individual’s life, but it is often difficult to interpret this data due to the similar results produced by different foods.

Based on these figures, we have concluded that although maize was consumed, it was not an important crop and probably made up less than 25% of the diet. The results of bone chemistry analyzes of the Machu Picchu remains provide a fascinating contrast. The results indicate that most of the carbon in bone collagen was derived from consumption by servants at Machu Picchu and, for most people, this constituted between 60% and 70% of the diet used to produce bone collagen. . Although remarkably high, this figure probably underestimates the importance of corn in the total diet.

While the importance of consuming chicha in Inca rituals has long been appreciated by scholars, the relative value of corn in the diet has been a topic of debate. Potatoes and other high altitude crops native to the Andes adapt to the mountainous environments of Cusco better than corn. Today, in the highlands of Peru, corn is still seen as a luxury consumed on holidays to break the tedium of a diet dominated by tubers. Among the Incas, associations of corn with the elite raise the possibility that, even if corn was the main food among the upper class, it may have been less important to the royal family’s servants and their guests than high-altitude foods. grown in associated planting, such as potatoes, quinoa and chocho (a type of lupine). The famous Inca scholar John Murra suggested that the prominent role of corn in Inca rituals reflected its special symbolic importance and association with the state, rather than its importance in daily nutrition. While Murra’s argument is plausible, the large sample and consistency of results from stable isotope analysis of human bones leave little doubt not only that servants and other staff at Machu Picchu had access to corn, but that it constituted the basis of your diet.

When corn is combined with beans, lupine and other crops, it is an extremely rich source of protein and other nutrients. The good health of the yanaconas of Machu Picchu, both men and women, was to some extent the result of this imperial diet. In contrast to a previous study of Inca provincial populations in the central highlands, no significant differences in corn consumption were found between the male and female population of Machu Picchu.

The central role of corn as a staple food of the Machu Picchu population is consistent with Verano’s findings in the Machu Picchu sample of numerous dental cavities, likely the byproduct of a corn-rich diet. Judging from the carbon isotope study, plant foods other than corn constituted a small but significant proportion of the diet. Unfortunately, stable carbon isotope analysis did not provide information as to what these products were. An alternative source of relevant evidence comes from microscopic pollen that has been preserved since the Inca occupation on the terraces of the eastern flank of Machu Picchu.

Pollen analysis is still rare in the archeology of the Central Andes, but has become more common in the last two decades. Because the structure of pollen is largely inorganic, it does not break down like most other foods. Depending on the composition of the soil, and despite heavy precipitation, pollen can remain intact for millennia. Following a study by Peruvian archaeologist Alfredo Valencia Zegarra and American hydrologist Ken Wright, soil samples were taken from the agricultural terraces on the slopes of Machu Picchu and pollen was extracted. When analyzed, the results indicated that the crops on these terraces included potatoes, an unidentified legume, and corn.

During the dry season, daily life at Machu Picchu was probably focused on the royal family and their needs. The public architecture that dominates the archaeological site continues to provide evidence of the public and private aspects regarding the activities necessary for the maintenance and entertainment of these individuals; while the yanaconas of Machu Picchu, who made up the majority of the site’s inhabitants, mainly served as support for the elite population, but also engaged in other productive activities. These routine tasks are reflected in the artifacts recovered at Machu Picchu. One could speculate that such productive activities may have been more intense during the months when the country palace was not visited by the royal family. Among these secondary activities, there is textile production, as certified based on the presence of spinning wheels for spinning and bone tools for weaving (known as Wichuña in Quechua) and lithic production, according to the presence of small objects of shale in the process of carving. Metallurgy seems to have been especially important at Machu Picchu.

The site is well located for this activity due to the presence of an abundant amount of fuel, and its exposed configuration would have favored the use of furnaces and other techniques for harnessing the wind. Some of the best evidence of metallurgical activities at Machu Picchu comes from laboratory analyzes done on collections recovered by the Yale Peruvian Expedition of 1912. Of the approximately 170 metal artifacts recovered during the excavations of Machu Picchu, 15 have been identified such as stocks of pure metal, work in progress and waste materials resulting from metallurgical work. The detailed study of these pieces by Robert Gordon – a Yale professor specializing in the history of metallurgy – and his student John Rutledge has shed new light on the types of metallurgical activities that took place on the Pachacuteq royal estate. Most were related to the manufacture of tin bronze objects, a copper alloy linked to the Inca State.

During the settlement of Inca society for more than 100 years in the Inca city of Machu Picchu. Andean societies came together to organize the main agricultural and cultural festivities of their ancestors. Since it is located on a granite promontory surrounded by snow-capped peaks such as Veronica and Pumasillo, the sacred mansion of Pachacuteq was conceptualized as the largest area of rituality. The Andean priests were great wise men, who perfectly mastered the knowledge of astronomy, chemistry, medicine, philosophy, etc. They were trained as children in the great educational centers, and from there the emperor distributed them to all the territories of the great Tawantinsuyo, so that they could teach the next generations the Inca culture. According to the records of the first chroniclers who arrived during the Spanish invasion, they were able to note that the Incas were an agricultural society, and that many of their festive activities were determined by astronomical observations. For this, the Inca governor ordered the construction of Nomones, which are a type of stone pillars, which were built on the tops of the hills where the sun rose and set.

The Inca culture determined their days of the month based on the phases of the moon, so much so that they never celebrated their holidays on the wrong date. It is believed that the Inca emperor was able to visit Machu Picchu at least once a year, typical of one of the most powerful dynasties in South America. Curiously, it is known that before participating in these Inca festivities, everyone practiced fasting, as reverence towards their deities or totems. And then they proceeded to drink a sacred drink, mainly chicha or also masato. If the individual really wanted to transcend on the astral plane, perhaps some of the sacred drinks such as ayahuasca, San Pedro cactus from which the Mescaline, or also the seeds of Huillca, we can infer all this, since the ancient cultures before the Incas, it was always a common practice, the use of plants that generate a sensation of visions, the psychoactive substance being DMT.

Explore the Manu Amazon Rainforest & Inca Trail hike to Machu Picchu, you will enjoy the best adventures in Peru, exploring amazing inca trail routes and the best amazon wildlife with our local tour guides, in small groups.

The Lares Trek combines high Andean trekking with a chance for genuine interaction with the most isolated indigenous communities which keep the inca culture alive. Majestic glaciers, amazing glacial lakes, waterfalls, llamas, and alpacas.

Get to know the majestic city of Cusco, cradle of the greatest civilization in South America, the Incas and their great works of engineering, the citadel of Machu Picchu by train.

The top sights of Peru will leave all the family thrilled by the scenic grandeur, ruined temples, colonial cities, amazing inca trail to Machu Picchu, the Inca Lost City, once buried under the tropical forest which surrounds it.

Travel to Peru to retrace the steps of the Inca, Peru's fascinating ancient civilization. Travel from Cusco, through the fertile heartland of the Sacred Valley and to the magnificent Ollantaytambo ruins, hike the best inca trail to Machu Picchu.

The classic Inca Trail hike to Machu Picchu is one of the world's greatest hikes. Along the 45 km you will explore unique andean valleys, lush mountain forest.An exquisite architecture of the Inca sanctuaries, which will dazzle you for its fineness and location within the Andes.