Culture & Adventure

Culture & Adventure

trip overview

included

Trip Highlights

activities

accommodations

itinerary

faq

essential trip information

best season to travel

price & availability

Reserve Online

trip overview

included

Trip Highlights

activities

accommodations

itinerary

faq

essential trip information

best season to travel

price & availability

Reserve Online

CREATING AUTHENTIC TOURS IN PERU

CREATING AUTHENTIC TOURS IN PERU

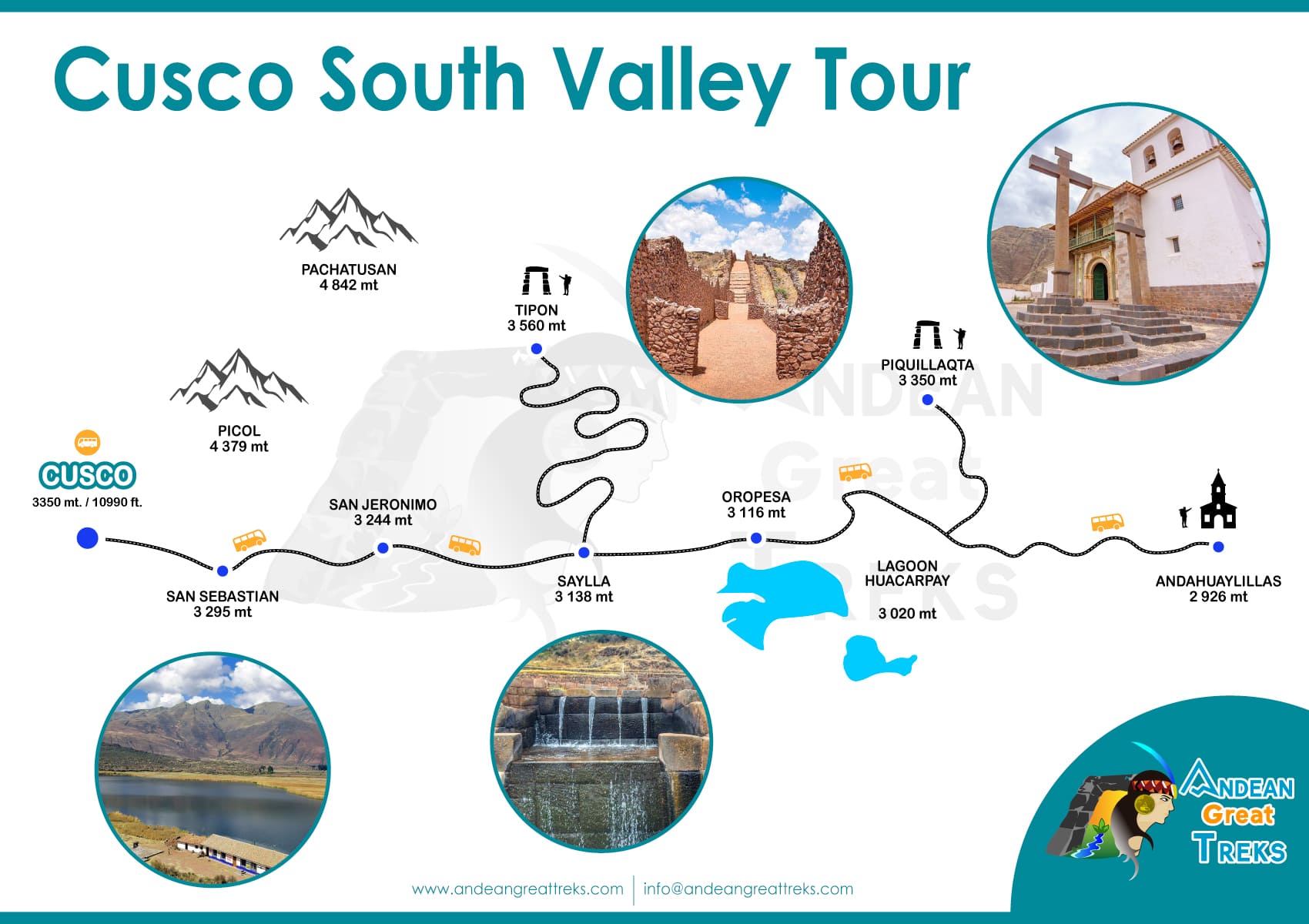

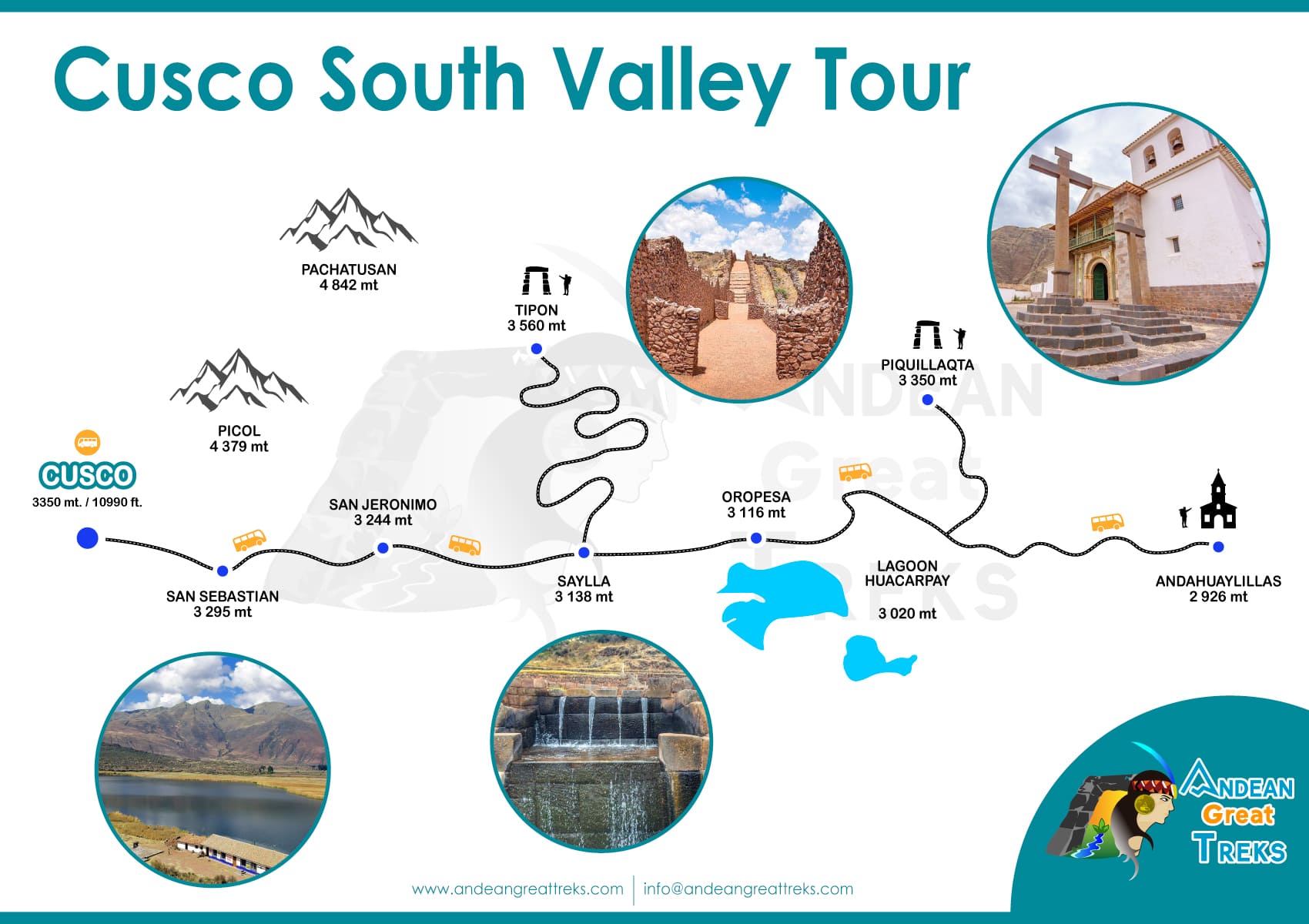

Explore the South Valley of Cusco. And the oldest still inhabited city in South America. In this long south valley of cusco with more of than 15 km, in the last stage of the glacial period of the Pleistocene, it was occupied by a large lake, whose name is from a researcher “Lake Morkill”. The fossils found in various parts of the valley show that it was inhabited by the Plesitocene megafauna, such as Andean horses, giant sloths, mammoths, Paleolamas.

The first appearances of hominids in the Cusco valley date from 8,000 to 10,000 BC. This is how these men become sedentary hunters and gatherers, and then form the first local cultures such as Killque, Chanapata, Qotaqalli, Marcavalles. Between 200 and 500 AD, the Tiahuanaco ethnic group invaded the valley of Cusco, and during 800 AD, this fertile valley was conquered by the Wari empire.

Those who make one of the largest constructions of urban settlements and roads in southern Peru, part of that great Wari city is still possible to appreciate in the archaeological site of Pikillaqta. In 1200 possibly the first regional confederations of the Incas appeared, as a local culture, centuries later it would become the largest empire in South America, they made one of the hydraulic wonders still in force until today in Tipon. With the Spanish invasion, the religious congregations imposed their religion, and the construction of the most lavish Catholic temples in architecture and arts, such as the famous Cusco school, many of these artists were the indigenous people who captured their art in the Sistine Chapel of Andahuaylillas.

Our transfer will visit you at your hotel between 08:00 hrs. to 08:30 a.m. Approximately to transfer you to the starting point of the tour. We will make a 40-minute trip to the southwest of the city of Cusco. We will start by visiting TIPON, which is part of the Qapaq Ñan route and is located 25 km from the city of Cusco, Tipon is a set of agricultural terraces, long stairs and canals carved in stone, its thirteen terraces are surrounded by polished stone walls. perfectly.

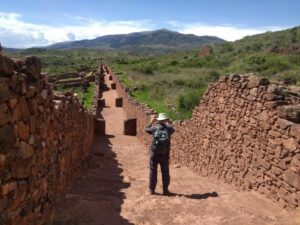

The greatest attractions that Tipon has are the royal enclosures, the Intihuatana also known as the altar of the sun, the viewpoint or cruzmoqo that is located in a strategic place from where you can appreciate or visualize the city of Cusco, the smaller enclosures and the wall it was built in order to protect the invasions of hostile peoples. Then we will go to PIKILLAQTA which is located 30 km southwest of the city of Cusco, Pikillaqta is currently known as one of the most famous and best preserved cities of the pre-Inca period in Peru and has an area of 50 hectares. about. The word PIKILLAQTA comes from two Quechua words PIKI (flea or small) LLACTA (town) and its translation could be Pueblo de Pulgas or Pueblo Pequeño. In Pikillaqta we can appreciate stone walls of pre-Inca origin and one of the most important cities of the Wari culture.

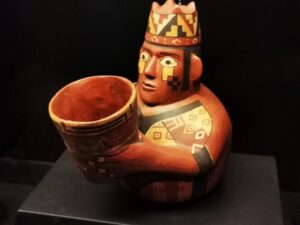

There is also a local museum, where there is an exhibition of the funerary and cultural elements of the Lord of Vilcabamba, who was a Wari ruler. Likewise you can see the fossil remains of an ancient Glyptodont.

Finally we will know ANDAHUAYLILLAS located 36 kilometers from the city of Cusco, Andahuaylillas is part of the Andean Baroque Route and its incredible Chapel better known as the Sistine Chapel of America due to its beautiful woodwork, beautiful paintings and colonial decorations.

On the return route, if you wish, you can buy the most famous breads in Peru, we refer to the CHUTA DE OROPESA bread, this delicious bread is an emblem of Cusco, due to its flavor and texture. You can also taste the delicious gastronomic dishes of Cusco, among them the Chicharron (well-fried pork), which is accompanied with its fried potatoes and boiled corn. Or if you want to experience the star dish of Cusco, the Baked Cuy, accompanied by a Stuffed Rocoto (it is the chili stuffed with minced meat, vegetables, and peanuts).

At the end of the tour we return to the city of Cusco, where our tour ends at 1:00 p.m. Roughly, the end point is Plaza de Regocijo, which is located just half a block from the historic center.

Check here the most frequently asked questions about the circuit, the south valley in Cusco. If you have any extra questions, you can do so by chat or email.

The South Valley of Cusco is the tourist name given to tourist attractions located southeast of the city of Cusco, between the provinces of Quispicanchis and Canchis. The most important tourist attractions in the South Valley are: the archaeological site of Tipón, the archaeological site of Piquillacta and the church of San Pedro de Andahuaylillas. Also in the South Valley you can visit Andean towns with many traditions such as: Huasao, Oropesa, Huaro, Urcos. The most famous natural landscapes are: the Huacarpay lagoon, the Pachatusan mountain, the Huasao wetlands and the Vilcanota river. To visit the tourist attractions described, you can make a trip on your own or hire a tour to the “South Valley of Cusco” that includes: Tipón, Pikillaqta and Andahuaylillas.

The South Valley of Cusco is in a geographical area made up of towns and natural landscapes located southeast of the city of Cusco. Most of the towns belong to the provinces of Canchis and Quispicanchis.

Tipón, one of the most touristic towns in the South Valley, is located just 25 kilometers by road from the city of Cusco. The archaeological site of Piquillacta is 33 kilometers away and the town of Andahuaylillas is 39 kilometers away.

The archaeological site of Tipón is at 3,560 m.a.s.l. The archaeological site of Pikillacta is at 3,350 m.a.s.l. The town of Andahuaylillas, at 3,122 m.a.s.l.

The South Valley of Cusco has a temperate to cold climate with temperatures that vary from a maximum of 23ºC. and a minimum of 3ºC.

The rainy season occurs from November to April, especially in January, February and March. The rest of the year, from May to October, is the dry season. In those months the nights are colder but the rains do not occur frequently.

The altitude of the places in the South Valley is lower than the city of Cusco, however, in order to avoid the symptoms of altitude sickness, we recommend you have an acclimatization time of one or two days in the city of Cusco walking without doing much effort.

Yes, previously having followed all the recommendations of our travel agents, in addition to the fact that children have a discount on some of the tickets and Tickets.

Also known as the Water Temple, it is 40 minutes by car from the historic center, a place where water was worshiped in Inca times, according to the chronicles of Garcilaso de la Vega, it was built by the ninth Inca or King Wiracocha.

Site that formed an important part of the network of Inca roads known as the great “Qhapac ñam”, cataloged by its construction as an agricultural experimentation center due to the design of the platforms and the impressive architecture of its underground channels, among these appeared the most outstanding of this place are the royal enclosures, where important people such as the royal family of the Inca lived, built on the basis of megalithic stone blocks within these are the water sources, irrigation canals and their beautiful gardens on the Inca terraces , other places like the Intiwatana known as the solar altar, are rooms built with trapezoidal windows where through the window you have a spectacular view of Tipon.

Tipon, a small town, a very traditional place in gastronomy in preparing a delicious baked guinea pig (guinea pig) by a local and at fair prices

The archaeological complex of Pikillaqta is located to the north of the Lucre river basin (south of the Cuzco valley), on the slopes of the Huchuy hill (at 3,250 meters above sea level). Pikillaqta differs from the other archaeological sites in the Sacred Valley of Cuzco due to its belonging to the Wari culture. Consequently, before presenting the Pikillacta site as such, the main characteristic features of this culture will be briefly evoked.

The Wari empire, the first in the Andes to be considered as such, flourished between 560 and 1000 AD (period known as the “Middle Horizon”). The chronicler Cieza de León mentions its existence in 1534, but it falls into oblivion before being discovered again in 1931 by the Peruvian archaeologist Tello, for which the archaeological investigations in the area are quite recent (1950s).

The current Wari archaeological zone is located mainly in the province of Huanta, department of Ayacucho, but archaeological investigations revealed that its influence extended from the Mochica zone to the north, to the Nasca territory to the south, that is, both in the mountains as on the coast of the current territory of Peru.

Chronologically speaking, Wari is considered to have had four stages of evolution: the first period is characterized by the emergence of the city of Ayacucho (25 kilometers from the current eponymous city) as a political and ceremonial center, under the influence of the Tiahuanaco region. In its second stage, wari knows an expansionist movement. It is the time of construction of Pikillaqta. Subsequently, the empire enters a period of crisis, which marks a pause in this expansionist movement, as well as population displacements, to which Pikillaqta apparently escapes. Finally, in its last years, Wari knows its maximum territorial extension. However, his capital soon collapses, as will be seen below.

The nature and staggering scale of the Wari expansionist movement have been the subject of much debate. Likewise, the Wari culture is considered the first in the pre-Columbian Central Andes to have implemented the pattern of development of urban centers from ceremonial centers. Its expansionist dynamic would later be inscribed in the context of struggles for political power between different cities. However, the main urban centers of this empire (Ayacucho, Cajamarquilla, Pikillaqta), would have managed to impose their power over an extensive territory, thanks to their impressive administrative organization and a series of technological innovations.

It is also observed that wari introduces in these areas the concept of fortified city, a novelty.

Its geometric urban centers, true centralized nuclei of administrative and economic power, consist mainly of rectangular enclosures with internal patios and plazas. On the other hand, this urban structuring revealed the existence of neighborhoods occupied by the elite, and also of sectors probably inhabited by servile labor. In fact, the Wari expansion meant a radical change in the settlement patterns of the conquered peoples. Likewise, the Waris displaced populations traditionally located in the highlands, towards the lowlands. They implemented population concentration in residential areas (replacing the previously dominant dispersed settlement pattern), and promoted the development of terrace cultivation, irrigation canals, as well as new maize varieties and road networks.

This political and technological dominance of the Wari culture is considered to have been accompanied by a strong religious ideology. Indeed, the dawn of the Wari empire was marked by a strong dry season, for which the implementation of new irrigation techniques was associated with the cult of a Tiahuanaco god related to fertility. It is perhaps for this reason that the expansion of urban centers from ceremonial centers is attributed to wari. What is certain is that the economic success achieved by this political-religious dynamic subsequently guaranteed a solid base for the Wari expansionist movement.

However: Pikillaqta constitutes a fortified archaeological complex that was inhabited between 600 and 900 AD. It is considered the largest and best preserved Wari site in southern Peru, something like a provincial capital. It occupies an area of approximately one square kilometer. The height of its walls is impressive, ranging between 7 and 12 meters. Some enclosures even have several floors, whose traces are still visible today. These walls were made of uncut stones, extracted from the surrounding mountains, bound with mud, and originally covered with a flattening of mud and lime.

The citadel itself was built around a rigid geometric pattern. It is surrounded by a wall and comprises 704 rectangular enclosures, some associated with elite dwellings, others with storage rooms or finally with some type of small religious/funerary cult centers. These enclosures are in turn grouped into blocks, each one surrounded by its own fortification and separated by roads, as a defense (let’s not forget that Wari is a society with a markedly militaristic tint).

It is thought that this grouping into blocks could correspond to a delimitation between different neighborhoods of specialized craftsmen. Indeed, Pikillaqta seems to have been an important commercial center, due in part to its location on one of the strategic axes of the Wari road network, as well as the presence of a large plaza at the entrance to the site, to which attributed the function of “tianguez” or place of exchange (although the possible ritual use of this square is not ruled out).

On the other hand, on the other side of the road that borders the site today, the presence of an impressive aqueduct associated with it can still be seen. This consists of several stone tiers, which are accessed by steps, and which were formerly linked together by channels for the circulation of water from the surrounding mountains, towards the citadel. In fact, an entire underground irrigation network was discovered in Pikillacta. This aqueduct was later reused by the Incas. Legend has it that its construction is the result of a competition between the gods.

The truth is that many mysteries remain around the knowledge of the fascinating Wari culture, and of Pikillaqta more particularly. The reasons for his abandonment for example: this seems to have been sudden, although organized. In fact, the entrance to several buildings was intentionally sealed, and, curiously, very little surface archaeological material was found, suggesting that the site’s inhabitants intentionally vacated it before abandoning it. Why? There are various theories in this regard, but none offers fully satisfactory explanations. The first, for example, -somewhat “academic” perhaps-, is based on the origin of the name Pikillaqta, from the Quechua “Piki” (flea), and “llaqta” (town). “Village of fleas”, since it is said that a plague of these insects would have forced the inhabitants to abandon the site. Other versions state that due to the commercial vocation of the town, there were simply many fleas in Pikillaqta. A final hypothesis proposes that the abandonment and reoccupation of sites were part of Wari political strategies, but the reasons for this possible strategy are not very clear at the moment.

This is just one example of the many unknowns that the mysterious Wari culture poses to archaeologists today. It is clear that the formation of this empire already heralds the emergence of the maximum state expression reached in the pre-Columbian Andes: the Inca empire. Therefore, a better understanding of the Wari culture would undoubtedly cast very valuable light on the roots of the Inca state, whose political dominance had repercussions that are even felt today.

Outstanding monument for the murals that are in this fascinating place with religious images that were conceived by the linguist priest Juan Pérez de Bocanegra, inside the church you can see a motto written in five languages: Spanish, Latin, Quechua, Aymara and the last league that was lost over the years, Pukina. Also inside the church you can see images with a didactic character that instilled in the indigenous or Incas to believe in the Catholic faith, it was built in two styles: the popular Renaissance exterior part and the interior part of European classic baroque style with an expression in fusion of cultures, the ceiling covered in a Mudejar style with floral and fruit creativity covered or bathed in gold leaf, all decorated in gold, carvings and paintings that amazes any visitor, built in the 16th century on an Inca building that is still preserves.

One of the aspects in which there is still no consensus is the beginning of the human presence in the American continent. However, despite the doubts and the limitations generated by the scarcity of old data, the interpretation that the arrival of human beings on the continent occurred in different waves through the Bering Strait is generally accepted. The data provided by archeology suggest chronologies that range from 30 to 50 thousand years. In the Andean sphere, doubts and lack of consensus are not the exception. The oldest dating that documents the human presence has been set between 18 and 20 thousand years BC.

This is the so-called Pacaicasa Man, discovered in Ayacucho in 1969 by Mac Neish. However, the data is not enough to establish this as the date in which the first men could inhabit the Andean region. Other researchers believe that it is more prudent to fix around 8,000 years later (around 13,000-11,000 BC) the oldest man in Peru, whose remains were found in the Ancash region: the so-called Guitarrero man. One thing that scholars do agree on is that for these chronologies (prior to 10,000 years BC), the Cusco valley still lacked human presence. As we saw in the previous sections, the current valley of Cusco was the bed of Lake Morkil, a lake that took the place of the Pleistocene glacial. Until recently, it was thought that the first inhabitants of the Cusco valley were farmers who lived in small villages spread throughout the valley (ca. 1,000 BC) since no evidence of human presence had been found in the archaic period. However, the work of B. Bauer in recent years, in particular the surveys carried out in the Cusco basin and the excavation of the Kasapata site, near Espinar (about 250 km south of Cusco), have made it clear that as in other regions of the Andes, after the retreat of the Pleistocene glaciers, prosperous cultures of hunters and gatherers developed in a chronology that extends between 9,000 and 2,200 BC

In summary, the new perspectives in archaeological research tend to place the beginning of human presence in the Cusco region in very early times. The so-called Yauri man (name with which the current Espinar was previously known) dates back to 5,000 years BC. Proof of the development of his hunting activities and the gathering of wild fruits are the remains of his material culture formed by projectile points and quartz, flint and basalt knives that have been documented in different places. A tool with complex functionality, intended to facilitate a mixed economy but which had already developed camelid grazing. The cave paintings of Virginiyoq are attributed to the development of this last activity, with the representation of scenes of camelids. In this same period, we find other human groups in the province of Chumbivilcas, whose culture spread occupying heights between 3,600 and 4,300 meters above sea level, thus being able to access the ideal ecosystems for grazing.

Also in this case, the presence of cave paintings with the representation of camelids confirms the domestication of the llama and its grazing. Likewise, their material culture is based on the manufacture of stone tools such as flint, jasper and quartz projectile points, which shows the parallel continuity of hunting activities. In the specific area of the Cusco basin, we can affirm that the archaeological documentation of the first archaic human groups is reduced to the remains of abandoned instruments. The small amount of remains and their dispersion in the valley suggest that they were occasional visits as part of hunting expeditions. It is necessary to underline that the archaeological documentation of remains left by the hunter gatherers of the archaic period is, in general, very limited. They were small bands that moved through the territory in search of game. Given that stable installations are scarce, since they generally formed temporary camps following the seasonal movement of game, it is very difficult to document their remains. Having only the projectile points recovered in the field surveys and the paintings and engravings of camelids, and the absence of documented stable settlements in the Cusco valley, makes it possible to argue that in these archaic phases (9,000-6,000 BC) the territory of the Cusco region was included in a migratory cycle of groups in search of hunting and gathering.

It will not be until 5,000 B.C. when the first stable camp in the area is documented: the already mentioned site of Kasapata. Thus, even though the place that the city of Cusco now occupies has hardly provided information on the archaic period (spear and arrow points made of lithic material), the archaeological data show that throughout all the stages of this period the region was scene of the presence of bands of nomadic hunters who traveled the territory seasonally in search of subsistence resources.Kasapata can be considered as a reflection of the progressive sedentarization of the groups, of the first forms of domestication and grazing of camelids and, it is possible that also, the birth of some forms of incipient agriculture.

THE VILLAGE COMMUNITIES IN THE CUSCO VALLEY: FORMATIVE PERIOD

The Early Formative:

It will only be with the so-called Early Formative (2,200 BC -1,500 BC) of the traditional division of Peruvian chronology, when we can find remains of the first sedentary villages in the Cusco area. They will already be small farming villages that reflect for the first time the presence of well-settled human groups in the valley. In the Cusco region, there is evidence of the first crops around 2,200 BC. Samples taken in the Maracocha lagoon show that agriculture was already part of these cultures and in this sense the burning of forests as a practice of agrarian land preparation has been evidenced.

Another indicator of human presence in the area is the pottery found and its specifications. For B. Bauer, the use of sand as an additive (degreaser) to improve the properties of the clay suggests that this is “the earliest pottery in the Cuzco region.”

The Middle Formative: The Marcavalle culture

The radiocarbon analyzes carried out with materials associated with the “Marcavalle” pottery suggest a dating that begins around 1,200 BC. and that ends around 500 B.C. Marcavalle was not the only village settled in the valley and it is probable that other settlements existed at the same time, although they have not yet been documented. The sedentary settlement of Marcavalle, the oldest and best documented in the Cusco basin, is located in the central part of the valley. It was formed by a community of farmers and shepherds dating from around 1,000 BC. It was discovered by the archaeologists Manuel Chávez Ballón and Jorge Yábar Moreno in 1949, although the first archaeological excavations were carried out between 1963-1964 by Luis Barreda Murillo. Karen Chávez conducted an extensive study of the materials recovered from surface surveys and archaeological excavations. We do not know in all its details the social implications of the appearance of this new cultural group in the valley, although the recovered cultural objects already show an important qualitative leap: the hunter-gatherer bands had been replaced by village groups that dominated agriculture. According to data from archaeological excavations, when they settled in the Cusco valley, the new inhabitants found good conditions for the cultivation of beans and corn, which stimulated their tendency to develop sedentary lifestyles. These same data suggest that they already had domesticated camelids for use as pack animals and a regular supply of meat for consumption and fibers for the production of fabrics.

The presence of other domesticated animals such as guinea pigs and dogs was also documented. From the point of view of the material remains found, Marcavalle pottery is characterized by the predominance of brown and red. Bowls with handles, pitchers with a side handle and plates have been found. In the Andean context, the puma, the condor and the serpent are sacred animals and Marcavalle pottery uses them as the main motifs in the decoration of its pottery. The architectural remains found so far allow us to speak of small-sized enclosures, rectangular or circular in shape, built with stone walls in which mud mortar has been used for gluing.

Adobes have also been found. The roofs of these enclosures had to be made of straw supported on simple structures of round wood.

Late Formative: The Chanapata Culture

The Chanapata culture developed in a later phase than the Marcavalle culture (500-200 BC). Both were village cultures that exploited territories with very limited scope for expansion. It receives this name from a type of pre-Inca pottery found by the American archaeologist John H. Rowe in his work carried out in the Cusco valley in the 1940s. It was called “Chanapata” as it was documented in that locality located in the Cusco neighborhood of Santa Ana. A second settlement within the valley was documented in the Wimpillay area, west of the current city airport. Both excavations documented walls, ceramics, animal bones, and burials. The study of the regional distribution of Chanapata ceramics documents the expansion of this cultural group outside the Cusco valley. This is corroborated by both the findings of Bandojan near the current population of Anta located about 20 km west of Cusco, and those of places near the current Paucartambo, a population located north of Cusco, a key site for entering the jungle. (yunga).

Chanapata domestic architecture did not differ much from Marcavalle: circular houses whose walls were built by slopes of earth and grass and covered with thatched roofs. In the excavations of Santa Ana, pieces were found that, due to their importance, allow us to connect this culture with other previous developments in the Andes. An example of this is a zoomorphic representation carved in stone that represents one of the oldest deities in Peru: the puma.

The pottery found in red and gray colors, decorated with animal and geometric motifs. The Huacoto quarries, located at more than 4,200 meters, on the northwest face of the Cusco valley, exploited prior to the Marcavalle culture, provided material for the making of sculptures and utensils for daily use. In summary, the development of the first village cultures (Marcavalle and Chanapata) reflects the progressive occupation of the different ecological levels of the territory. The different heights of the valley were occupied to access differentiated agricultural resources that, if they had been concentrated in a single place, could not have been obtained. In short, the beginning of the integral exploitation system called the vertical archipelago. The integration of the family structures of the valley in the state formations The Marcavalle and Chanapata cultures correspond to the definitive development of agriculture and livestock in the mountainous area of the interior of the Andes.

The old hunting bands give way to much more complex groups from a social and technological point of view: they are the first village societies that, throughout the first millennium B.C. They arise in the isolated valleys of the interior of the mountains, particularly on the slope that goes towards the Amazon, as is the case in the Cusco region. Although it is not very evident in archaeological terms and we speak in general of fragmentary communities, it is possible that in this period each valley already had a main settlement. These changes should be related to the processes of cultural transformation that had been taking place several hundred years ago both on the coast and in the north of the Peruvian Andes. Groups settled there that were able to build monumental ceremonial complexes that brought together the agrarian population, usually dispersed on farmland. These centers congregated a seasonal population and come to acquire authentic urban functions during the markets developed for the great festivals.

Archeology already documents before the change of era the circulation in the Andes of prestigious goods from the warm seas of present-day Ecuador: seashells (strombus) intended for use as a musical instrument (potutu) or pearly shells as ornamental objects ( spondius). The initial scenario, the coastal valleys of the Andes, show how sites such as Caral have been the expression of the expansion of monumental forms of architecture since the Archaic Period in chronologies from 3,000 B.C.

These immense ceremonial sites are the expression of the progressive complexity that the state organization acquires. The valleys, such as the so-called Callejón de Huaylas, which allow the transverse circulation of the Andes and reach the edge of the jungle and the jungle itself, are the context in which the Chavin culture will emerge, capable of expanding its influence throughout the Peruvian coast. This culture is an exponent of a complex development thanks to intensive agriculture produced by large human concentrations organized in more stratified social structures. The contribution of the coast will be the agricultural technology that will allow the growth of the population and, in turn, will be conditioned by the greater availability of labor. Extensive agriculture would use a technology whose degree of sophistication took it to its minimum expression. The population will be organized for the opening of canals and the transformation of the valleys crossed by the rivers into authentic orchards. The development of architecture and a sophisticated visual culture will be the effect of the progressive transformation of these complex societies. Parallel to this situation, in the valleys of the interior of the Andes directed geographically towards the jungle we speak of later chronologies. The difficulties inherent in the environment hindered the expansion of the sedentary societies that would emerge during the first millennium BC.

Thus, the image that we can make of these is as agrarian societies that barely surpassed the stage of fragmentary groups, atomized by the effort of survival in a much more difficult environment than that of the coast. For example, the natural environment of a valley like Cusco cannot be controlled by small communities. Intensive rains are seasonal and it is not enough to open channels, it is also necessary to conserve water. The land presents a huge slope and the agricultural exploitation can only be intensified with a very sophisticated system of terraces. While on the coast several cultural developments for several centuries had implemented extensive irrigation systems, the mountain is still tied to the grazing of camelids and small farms of different vegetables adapted to the different ecological levels.

The fragmentation of the forms of exploitation of the territory will force the communities to develop forms of reciprocity, solidarity and integration. Thus, during the so-called Formative Period, structures were consolidated in the interior mountains that would end up becoming the basis of the social organization of the Andes: the ayllu system. Commented on previous pages, this structure of family origin established kinship relationships between its members who considered themselves descendants of a common ancestor. The members of an ayllu acted simultaneously on different ecological levels.

In Inca times, the ayllu was the basic unit at the administrative and control level of the territory. All of them contributed labor (mita) from among their components to carry out public works such as the construction of bridges, roads and buildings. They had a chief or curaca, who was a judge, organizer and administrator. The distribution of land, collective work and the legal order of the community depended on him. In the case of Cusco, the development of these organizational forms will have its cultural effect in the appearance of the first political groups with a certain regional influence. From the struggles between the local ayllus, the dominance or supremacy of one of them was imposed. Confrontations and alliances ended up establishing a certain sense of community that came to control the valley of the Cusco basin, at first, to later extend to a region that went from the Anta zone to the northwest of Cusco to the Lucre basins. and Huaro to the southeast.

Between 200 and 600 AD, the appearance of the first regional state in the Cusco area has been dated: the Qotakalli (Bauer 2008). This is characterized by the appearance of a new style of ceramic production, and in turn represents the consolidation of homogeneous cultural forms that will extend beyond the limits of the Cusco valley. Some indications suggest that the area of influence of the Qotakalli culture would go to the vicinity of Lake Titicaca, 200 km south east of Cusco. During this period, prior to the emergence of the Wari state, the first water channeling and terrace projects could begin to be managed to increase the land as a result of the intensification of agricultural production. Regarding the architecture, it does not seem to have major variations with respect to the previous period: the structures are built with unpolished stones glued with mortar made from mud and straw. The buildings are rectangular in shape, about 9 m long by about 5 wide.

In the Araway area, a settlement made up of 40 structures of this type has been found.

It is interesting to note that on the Peruvian coast the early development of intensive agriculture is related to population growth and the formation of despotic-type state structures (although we do not know in what order the three factors occurred). A process that presents great analogies with what happened in other geographies of the world such as Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley or China (Yellow River). It is important to remember that inside the mountain range the process was later. The fragmentation of the territory into narrow and steep valleys led to the establishment of small-sized social forms through which survival would be guaranteed. The ayllus ensured their success as nuclear formations by basing their essence on group solidarity and reciprocity as a survival strategy. This determined their progressive transformation and they ended up integrated into forms of regional domination such as the Qotakalli. Although apparently they were not forms with a marked militaristic profile, like those of the coast, they opened the way to the formation of disciplined and organized societies much more rigid than the coastal ones, but also much more effective in an environment as harsh as that of the cities. Andean heights.

The Wari culture was the first great state formation that spread between the central Andes and the Pacific Ocean coast and was, along with Tihuanaco, the great culture of the interior highlands (Titicaca), one of the two most important cultures of the so-called Middle Horizon. . Its expansion began in the years 600-700, from an original nucleus located around Ayacucho and from the Huarpa culture. As a state political organization it lasted at least 200 years, however, the carbon dates provided by some deposits such as Pikillaqta suggest that it could have lasted even longer. The identification and interpretation of the Wari culture is a recent historical phenomenon. Let us remember that until the 50s of the last century this culture was considered simply as a manifestation of Tiwanaku on the coast of Peru.

However, archaeological documentation has managed to characterize it as a militaristic state that expanded rapidly outside the Ayacucho region: to the north it reached Cajamarca and to the south it occupied the Cusco region. However, we have to underline that there is no well-documented archaeological evidence of acts of military aggression by the Wari and that there are alternative interpretations to explain their expansion. For example, the one that underlines the role that religion could play in general and in particular the great oracular sanctuary of Pachacamac, on the central coast, as a factor that influenced its expansion.

In this sense, the spread of large Wari ceremonial urns, similar to those that were crushed and ritually buried in Conchopata near the Wari capital, has been cited as an indication. These are pieces very similar to the so-called “Pacheco urns” described by Tello (1942) and which suggest the powerful role that religion must have played in the Wari expansion. In fact, some specific authors consider the Wari phenomenon as a reflection of the expansion of religious traditions promoted from Tiahuanaco, whose diffusion should be related to the rise of the exchange economy. However, other authors propose an interpretation of an agrarian nature associated with the climate crisis that would have coincided with the beginning of the Wari culture.

In this sense, it is important to underline that the study of the ice deposits in the Peruvian snow-capped peaks places a great period of drought around the year 550 AD. This crisis would have pushed the Wari in search of new land and pastures. However, the most general vision understands that the Wari expansion was supported by a combination of religious and economic incentives, and emphasizes the spread of advanced agricultural technology based on the construction of terraces with irrigation canals. In any case, the Wari Horizon (540-900 AD) is characterized by an architectural style associated with the construction of monumental architectural complexes, the development of hierarchical administrative centers and the distribution of certain characteristic types of ceramics. The capital of the Wari state was located in the homonymous settlement located near present-day Ayacucho, a point from which its domain expanded. Some authors have estimated that its population was between 10,000 and 20,000 inhabitants, although they admit that according to archaeological data it could have exceeded 35,000 and even reached 70,000. In any case, it is accepted that during the Middle Horizon it was the largest urban center in the central Andes with an urbanized area that certainly exceeded 2.5-3 km2 (some estimates place its extension between 10 and 15 km2).

In the valleys of the interior Andean highlands, the Wari built large administrative centers: in the north Viracochapampa, in the south Pikillaqta and Jincamocco. On the coast, the Wari presence is documented through ceramics associated with funerary contexts, since hardly any Wari architectural ensembles are known. Sonay in the Camaná Valley and Pataraya in the Nazca Valley are two exceptions.

In the particular case of the Cusco area, Pikillaqta is located in the same Watanay valley and was a huge administrative settlement. It was built to control a strategic mountain range located near the border with Tiahuanaco. There are studies that several Wari settlements whose character could be administrative. However, the importance of Pikillaqta lies both in its dimensions and in the fact that it is the result of a planned action in its entirety. Archaeologist Gordon McEwan has been able to establish the construction sequences of the complex. He has identified 4 main sectors where 1 and 2 are perhaps the best studied. Sector 2 is the oldest and the most elaborate. It is made up of a series of large complexes and has a main square and a secondary one. Apparently, this sector underwent some kind of modifications throughout its history of use. Sector 1 was never finished, while sectors 3 and 4 are still in the process of being excavated and studied. A company of this size was unprecedented in this area of the Andes.

Pikillaqta was built with unworked local stone, joined with mud mortar. Walls and floors were at some point plastered with white plaster. Due to the way in which the high walls that surround the complexes were built, it has been thought that it was shift work (mita) that allowed the mobilization of a large amount of labor. This way of working would be very effective in Inca times. During the 300 years that the Wari presence in the Cusco area could last, we can trace other settlements in the territory apart from Pikillaqta. According to research carried out by G. McEwan, Pikillaqta was not the only Wari settlement in the Lucre Basin. To the south east, in the Huaro river basin, a Wari site of great importance has also been documented in which habitation sites, a cemetery with high-status tombs and an area with high-quality ceramics were found.

In turn, the researchers think that it could be from this basin that in early Wari times they began to consolidate their control in the Cusco region. Other Wari sites, both to the southwest and to the northwest of the Lucre basin, have been studied in order to establish an occupation pattern already in Pikillaqta times. The ceremonial site of Muyu Orqo, near present-day Paruro just 20 km southwest of Pikillaqta, is one of the few found in this area. To the northwest, in Valle del Vilcanota, the situation is similar, which suggests a very unequal occupation of the Cusco region during the Wari period. In the Cusco basin, the studies carried out lead us to think that there was no administrative center of a secondary nature in the area. It is not surprising that no such site had been established considering the proximity to Pikillacta. The Cusco valley in its entirety was to provide labor for the construction of the administrative city and its agricultural production was surely brought to it.

During the Wari domination, it is possible that there were fewer scattered settlements in the valley compared to the Qotakalli period and this is possibly due to the concentration of labor given the intensification of agricultural exploitation. It is also important to highlight that although there were changes, these did not mean a change in the general conditions of the model of organization and occupation of the territory by the peoples who already inhabited the Cusco region at the arrival of Wari. The Wari administrative strategy was to use the structures consolidated in previous times, both routes and populations. It is easier to control the existing dynamics at the product traffic level, for example, than to create new infrastructures to achieve them. They invested their energy in consolidating power and not in changing an economic and social system that was already favorable to them.

From our point of view, we are interested in highlighting that the Wari culture is associated with the development of ceremonial activities closely linked to the sacred conception of the landscape in connection with the cult of ancestors. We have enough examples that allow us to talk about the importance that this culture attributed to the topographical characteristics of sacred natural places. There is a typified narrative that is based on the cosmological conception of the world, where water is always associated with origins (the cave) and its control depends on ritual respect for cosmic cycles. The Inca society will collect all this several centuries later. The cult of mythical ancestors will be used by the groups as a justification for the use of water, since no one can possess nature. Therefore, groups must develop common ancestor myths that justify the group’s use of resources.

All this began several centuries before the emergence of Inca power in the Cusco region. In the Wari culture, as in the other cultures of the Andes, there is a close relationship between myth, use of resources and settlements. The lakes and water sources as points of origin of a town (or pacarinas) is a figure that also appears in the case of the great capital, Wari, near present-day Ayacucho. It has been suggested that the nearby Conchopata lake would be the mythical pacarina from which the Wari would have emerged. In turn, it was the lake that fed the city through a system of canals. In the Cusco region, the distribution of the main settlements of this period also has an evident relationship with water. Pikillaqta is situated next to the Huacarpay lagoon and a system of three aqueducts supplied water to the terraces. The Huaro deposit, 15 km from Pikillaqta, was located next to two lagoons. K’ullupata, located 35 km from Huaro, also arose near one.

Pachacamac, the largest site built during the Middle Horizon on the central coast of Peru, served as a sanctuary or huaca and oracle from 200 B.C. The sanctuary is situated on the edge of the Pacific Ocean. The great prestige of it as a center of pilgrimage in all the Andes made Sapan Inca himself adopt it as the huaca of his origin when he joined the Inca. It is one of the two main Upaimarcas (or pacarinas) of the Inca. Votive objects dating from the Middle Horizon already show their importance in the Wari period. Another interesting example is provided by the Wariwilka sanctuary, associated with the Wanka ethnic group. This is the traditional myth of the Andean origin that archeology has been able to materially document. A large, almost square enclosure (45 x 48 m) has been found, with double walls that included a passageway between the two walls and three entrances preceded by stairs. Inside the enclosure there is a natural spring with several distribution channels that led the water to the outside.

It is probably the “puquio or eye of water” that Cieza de León cites. Attached to the interior of the enclosure is a series of rooms, and some rooms inside the enclosure must correspond to the cult space of the sanctuary. The archaeological materials show that from the beginning of the Wari period the sanctuary received abundant offerings, and that it was probably already the seat of an oracle and had established hierarchical relations with Pachacamac. All this seems to corroborate that it was an ancestral sanctuary already in use by the Wari, confirming the symbolic relationship between the water, the mountains and the oracle as spokesman for an ancestor.

Near the great Wari site of Viracochapampa we find Cerro Amaru, a place belonging to a local group but which was frequented by the Wari. In 1900 Max Uhle excavated one of the pits and documented its use as a sanctuary, and it has been interpreted as a ceremonial center. Numerous offerings were found including thousands of Dumortierite, Turquoise and Spondylus shell pearls, large Spondylus roughs and worked. A large mausoleum was found at the site with two privileged burials arranged on a bed of Spondylus shells. Along with them, several secondary burials of characters belonging to elite families were documented. The burials are associated with Wari pottery. All this has led to the belief that it was a sanctuary for the worship of water related to an elite lineage.

The Cerro Amaru wells are reminiscent of the Teqsecocha huacas in Cusco. Teqsecocha can be translated as “origin of the lake” in Quechua and they commemorated the founding of the city. Some authors have argued that they must have been waste from the wetlands that were dried to establish the city. Perhaps fenced and constructed “mini-lakes”, huacas that commemorated the Inca foundation of the city. If we consider these models, the Cerro Amaru water wells could symbolize the cosmological origin of the ethnic group. The funerary chamber would have been intended for the rest of the founders of the lineage. These data suggest that the sanctuary was already fully operational in the Wari period. The association of wells and ancestors suggests the importance that Cerro Amaru acquired from the point of view of the cosmological symbolism of water management.

In this sense, the relationship of Viracochapampa with Cerro Amaru suggests that the ritual wells played an important role in the Wari expansion. The religious attention paid by the Wari to lakes and water sources was part of the landscape control system inherent in the Andean religious conception. Ultimately, of course, it was an agrarian resource. In this sense, all of this must be associated with the large-scale agriculture that the Wari deployed for the first time in the mountains. These lakes were the Upaimarca pacarinas of the ethnic groups that had come under Wari control. The attention they received from the new administrators demonstrates their integration into the new models of farming. It will be important to take the above into account, since the characteristics of this wari model will be easily identifiable in the Inca case. There is a certain consensus that in the Inca period, depending on the type of social organization, the type and size of the new administrative structures were considered.

Members of the local elites were incorporated into the Inca administrative system and the local structures were left intact. Sites with weak or nonexistent administrative structures would lead to the construction of new administrative centers. The alliances with the elite families in the Cusco region would be of vital importance at first, since the Wari needed the labor that would allow them to build the gigantic administrative city of Pikillaqta. At the end of the first millennium, the Wari empire disintegrated. As with the end of Inca domination in the Andes, Wari administrative centers like Pikillaqta will be quickly abandoned. We are talking about centers with a small fixed population, with elites that had no family ties to the territory and where the administered populations went to the great administrative center only to pay tribute through work. Without the dominance of imperial power, these great urban centers had lost their reason for being.

The formation of the Inca State is a company that for a long time was seen as the product of a single factor: war as the only element of conquest and subjugation. However, a new interpretive framework has made it possible to understand that there were multiple causes that influenced the success of this company.

Thus, the Inca domination over the different ethnic groups that inhabited the valley was due to factors understood as long-term processes, and not only to the continuous dispute over territory. These factors allowed the modification of the relations between the groups generating new alliances and forms of exchange. Although there is no consensus regarding the events that favored the emergence of the Inca state, little by little the conception that a single person was the generator of the political, economic and social transformations that resulted in the formation of the Tawantinsuyu has been changing.

Although the foregoing opens new perspectives for the study of the processes that led to the union of the territory during the first phase of Inca rule, one should not go to the extreme of downplaying the great Inca figures who, like Pachacuteq Inca Yupanqui, knew take advantage of the moment they were living and the conditions they encountered in their path to form alliances, reach agreements or exercise submission. The rise of Inca power in the Cusco area is apparently linked to the vacuum left by the fall of the Wari empire around 1000 AD. Although we are talking about a period of nearly 400 years, it is key to understand that the change that this event brought about in the political system would be felt in the way in which the different ethnic groups that inhabited the territory would relate to each other.

During this period called Killke, the Cusco basin will undergo important physical transformations caused mostly by the increase in population in the plain and the occupation of other sparsely inhabited sectors. This is the case of the northern basin that had not been inhabited before and in which numerous settlements are beginning to appear; It had not been exploited either, given its geographical conditions, a very rugged terrain due to the canyons that form the streams, and in this period it was transformed for agriculture through a system of canals and terraces that would allow its exploitation. In a very well studied process in cultures from other latitudes, and easily extrapolated to this particular case: the surpluses provided by the new “land bank” that constituted the terraces, allowed the emerging elite of the Cusco valley to establish a system of payment of favors with other local groups.

Both the expansion of the fields and the use of the mita (rotating and forced labor that is organized for the construction of works and the cultivation of the land) will constitute a model that will result in the enrichment of the elites. In later phases, with the growth of the Inca control area and the consequent increase in the amount of labor, the great works will be carried out at the regional level thanks to the labor force concentrated during the periods between planting and harvesting. Projects such as the channeling of the Urubamba River, the large irrigation systems or the large extensions of terraces found throughout the Cusco region were only possible thanks to this way of organizing the population and work.

The way in which the valley was dealt with is another aspect that has been studied as an indicator of the moment in which the Inca culture became a regional power. Strategies such as the relocation of subjugated populations or the displacement of populations seeking protection were implemented to increase productive capacity and eliminate redundancies in hierarchies. This occupation in the early stage of the formation of the Inca culture as a political entity has been estimated to be more or less the same as that of the Inca state at its time of maturity. Indications have also been found that in the early stages of the Killke period some groups in the area of influence of Cusco were not relocated from what follows that these strategies are consolidated as the power of the elites increases and new strategies are generated. of control.

The resources produced by the valley were controlled by the Inca elite, generating a system in which the groups that lived near the productive lands received certain benefits in exchange for commitments established with the curacas, “lords” of the State. In general, and for each of the regions outside the Cusco basin, it has been possible to document the ethnic groups that inhabited them and with whom the Incas established alliances or domain relationships. Perhaps the most important case of alliance is that of the Anta and Ayarmaca ethnic groups who, through the exchange of daughters between their elites and the Incas, established a certain territorial balance.

The main wives of Incas like Yahuar Huácac (seventh ruling Inca) was the daughter of an Ayarmaca lord. It is worth saying that during the early Killke period there were regions such as the territory between Ollantaytambo and Machu Pichu that was not included within the Inca domains and proof of them are the Cusichaca valley deposits located in places of very difficult access and prepared for defense . Another case is that of the area occupied by the Quillisachi ethnic group, who lived near the current town of Huarocondo to the northwest of Cusco and in which there are fortified sites from the Killke period, such as the site of Huata. Another aspect on which the archaeological works allow us to reflect is that the idea of the permanence of a constant state of war during the period of Inca expansion in the Cusco region is not true.

Kenneth Heffernan (1989) has worked in the Limatambo region, 50 kilometers west of Cusco, and has found that, like the situation south of Cusco, few, if any, villages are fortified. . Although, as in the rest of the valley, there was a displacement of the population, this did not involve a continuous struggle. To understand the diversity in the processes that led to the Inca domination of the territory and the changing strategies of domination, the case of the Huayllacan, an ethnic group that inhabited the territories to the north of the valley, is illustrative. Apparently there was a first stage in which the Huayllacan were progressively integrated into the Inca administration through marriage alliances. However, and perhaps due to their continuous attempts to free themselves from Inca control, they were never admitted into the restricted group of privileged Incas. In a later stage, the Cusco elites would be the ones who would directly exercise power over their territory.

A similar case is that of the Cuyos who occupied the basin north of the Pisaq site. According to chroniclers such as Sarmiento de Gamboa or Santa Cruz Pachacutic Yamqui Salcamayhua, the first territorial expansion undertaken by the Incas occurred during the reign of Cápac Yupanqui (fifth Inca) in which the Cuyos ethnic group fell. The dynamics that led to this conquest may have been related to issues such as trade and the worship of a specific deity.

It is only until the reign of Pachacuteq that the name of the Cuyos reappears. These are falsely accused of attacking the Inca Pachacuteq and sent to remote regions for coca cultivation or incorporated into the workforce that participated in the great works for agricultural exploitation in the Vilcanota Valley. In the same Cuyo basin we find an example of how ethnic groups with a strong administrative development remained in the area of influence of the Cusco Valley.

This is the case of the Pukara Pantillijlla settlement. This heavily terraced hillside site appears to have had its heyday between 1250 and 1350 AD. long before the Inca regional domain, and it is clear that it fought for its autonomy at the time of the first Inca expansionist companies.

In the southeast region, in the area known as Lucre, the Incas would fight against two ethnic groups: Mohina and Pinahua. Sarmiento de Gamboa narrates how, during three or four different reigns, the Incas razed the main settlements of these ethnic groups for considering themselves as “free and they would not serve them, nor be their vassals.” The displacement of the population and the occupation of the territory were some of the strategies used to control the territory. The chronicles collect the claims that Pinahuas made to the Spanish conquerors so that the territory occupied by the Incas would be returned to them.

Chronologically speaking, it seems that the Pinahuas filled the void left by the disappearance of Wari control in the area, since Chokepukio is the largest settlement of the so-called Killke Period. In this same period the size of Cusco could be similar to that of this settlement.

Meanwhile, there are more problems to identify the territory occupied by the Mohinas who are believed to have inhabited the southern part of Lake Lucre. In colonial times they would be relocated near Oropesa, in the middle of the Cusco and Lucre basins, since the Spanish conquerors perpetuated the right over the possible Mohina lands to the descendants of the Incas. The Oropesa basin, the intermediate territory between the Cusco basin and the Lucre basin, at the fall of Wari suffers from depopulation at the foot of the valley and the only settlement is established in the hills about 900 meters from the base of the valley. This site, known as Tipón, also has a protective wall and is considered the only example of a fortified town in the Cusco area. This is perhaps a sign of how this region becomes a zone of separation and/or clash. This situation continued until the domain of the region by the Inca was so great that the populations of the Lucre basin ended up falling. All of the above paints a picture in which, faced with the multiplicity of variants (ethnic, linguistic, and political), the Incas developed the same number of strategies with more or less success.

For example, the resettlement of the population sought to erase the concept of local identity, with what this meant at the level of traditions and beliefs; a practice widely implemented in the early development of the Inca state in the Killke Period. Going from a regional to a continental state meant that the strategies were maintained over time only based on their results within the political structure of the new state. Inca power was never constantly on the rise since, even in the period of maximum territorial expansion, alliances created between an Inca and another ruler could be broken upon the death of the first. In turn, military companies depended on a physical structure that could vary over time.

In the preceding pages we have briefly summarized the progressive acquisition of the historical role of the Cusco Valley as the origin of the Incas. It is a process that, as we have seen, presents more doubts than perhaps certainties. However, there are some important aspects that allow us to understand the profound meaning of the choice of Cusco as the capital; the place from which the network of roads that organized territorial relations started.

Certainly, the Inca power was able to build an extraordinary communications network for its time. Its two main axes, which united the four suyus or territorial districts of the State, converged in the great ceremonial plaza that organized the center of Cusco. These four axes intersected at an almost right angle and determined the guidelines for the layout of the streets of the capital city. Spanish chroniclers also remind us that the city was designed to be seen from the sky in the form of a recumbent puma.

In this ideal scheme, the city concentrated innumerable sacred places (huacas) and cults from all corners of the Tawantinsuyu. Its buildings housed the efficient administration that allowed the operation of the entire system with the Sapa Inca at the head. Finally, the Inca oral tradition from which the chronicles of the colonial period are nourished, and which ultimately present us with this image, attributes the design of this ideal model to Pachacuteq Inca Yupanqui, the ninth ruler who defeated the Chankas, traditional enemies of the Incas and extended their domains to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. The construction of this model, as we have seen in the preceding chapters, is the result of a complex historiographical elaboration.

It was born in the first place from the idea that the Cusco elites themselves had of their own conscience as a state. The establishment of the capital of the regional state in which the Inca power had become, on the site where the city of Cusco stands today, was the conclusion of the process of political integration of the Andean territories. The key figure was of course Pachacuteq. Despite the historical problems that his figure poses, well explained by M. Rostworowski, he is the great character that will remain in history as the one who devised a territorial system that allowed the Inca domain. For this reason (the Spanish chronicles) it is believed that it was also at the time of this Inca ruler that the city was laid out as the Spanish conquerors would see it. The idea that the city from a bird’s eye view had the shape of a puma would have been conceived as the starting point of the four paths that formed the base of the Inca Trail and that extended throughout all the territories under domain of him. Finally, to understand the role assigned to Cusco as the material and symbolic center of this system, it is necessary to take into account that the Inca culture incorporated preceding traditions and organizational forms whose success and effectiveness had already been proven by other political organizations, in particularly the Wari.

Certain practices of reciprocity such as mink’a and ayni already had extensive application in the Andean sphere. In the field of civil works, since the time of the Middle Horizon (particularly with wari) long roads had been built with important bridges, even equipped with tambos or “inns”. In addition, it is probable that the Wari had already proceeded to move populations based on their interests, as suggested by the shape of the Pikillacta settlement, and it is possible that they already had servants similar to the Yanas institutionalized in the Tawantinsuyo. The Incas were able to integrate all this into a new system extended this time to the entire Andes.

As we will see in the following chapter, the complex center of all this was the City of Cusco. The Tawantinsuyo was the most extensive state formation that came to be constituted in all of America before the arrival of the Europeans. The geography subject to the authority of the Sapan Inca covered almost all of Peru, including the coastal lands, the mountains and also the so-called “brow of the jungle”. Through the north of South America, it reached a vast territory that reached the city of Pasto in present-day Colombia, the entire territory of Ecuador. To the south, it extended through the Bolivian highlands and mountains and included the territories of northwestern Argentina and northern Chile.

We have to remember that the expansion of the Incas through the Andes took place in just eighty years. During the government of Pachacuteq, Tupac Inca Yupanqui and Huayna Cápac, some centralized and well-organized administrative states such as the Chimú, territories controlled from powerful sanctuaries such as Pachacamac, a multitude of territories governed by curacas and a large number of organizations were incorporated into the Tawantinsuyo. social groups of all kinds that inhabited this extensive territory. On some occasions they did so voluntarily as a result of a negotiation. However, in many others they did so due to the coercion of the well-organized Inca army or as a result of a true war of conquest and subjugation. To understand the political determinants that conditioned this process, the new works published in the last decade are fundamental. The publication of the immense archaeological dossier and the new orientation that its study has taken, as well as the review of the large number of colonial documents from the archives, is defining a new historical panorama that determines the general revision to which historiography is subjected. inca

The process of formation of the Inca state and its unstoppable military expansion resulted in the political unification of the Andean area, the last phase of the development of Peruvian societies before the arrival of the Spanish. Its arrival cut short this process, which not only failed to consolidate itself as a complete unit, but also its basic weakness allowed its rapid disappearance. The new data suggest that this process had begun to be implemented since the Wari era in the Peruvian highlands.

Likewise, the past of the Inca ethnic group before its expansion out of its primitive nucleus emerges more and more clearly. The Incas, like the other peoples settled in the Cusco and Urubamba valleys, were part of a Quechua macro-ethnic group since they shared the language and many of the cultural, social and religious traditions. As we pointed out, the chronicler Juan de Betanzos indicates the numerous ethnic groups settled in the Cusco territorial environment. It is not surprising that this political fragmentation was resolved with conflicts and confrontations that Inca history had preserved through oral transmission and that was collected by the chroniclers. The Incas were able to group these groups under their rule, on some occasions as a result of military conflicts, but on others taking advantage of the mechanisms of reciprocity implicit in the Andean collective mentality.

Some chronicles of the colonial period emphasize that the Inca power was established with violence and that the defeated populations were repressed with a centralized, arbitrary and despotic state policy. Although on many occasions the Inca conquest can be seen in this way, we cannot ignore that these writers projected in their descriptions the functional model that had served to shape the European empires of modern times. In reality, they could not understand that even in cases of conquest with acts of violent warfare, Inca domination would hardly endure if it were not based on Andean principles of reciprocity. There is another factor that influences this perspective: the Inca army was not permanent and could not function as a stable force of repressive occupation. Military campaigns, both those aimed at conquering new territories and those aimed at punishing insubordination, rebellion or breaches of reciprocity commitments with Cusco, had to accommodate the seasonality of agricultural activities.

Given the short time that the Tawantinsuyo had to develop, it is likely that this design responded to a system of thought built from the center of power in the first years of its expansion. Let us remember that the Quechua language itself was transformed in order to serve as a common language and allow communication between the ethnic groups that had their own language but had been integrated into the Tawantinsuyo. Quechua, as a vehicle for the Inca ideological program, sought to integrate all aspects of the complex Andean reality into a unified system. The chroniclers of the colonial period do not tell us, but we can assume that the objective was to ensure that all the ethnic groups integrated into the reciprocity system appropriated it, contributed to its dissemination and participated positively in its construction.

The expansion of the Tawantinsuyo caused the power of the Inca to increase as the population and the conquered territories increased. Although originally reciprocity had been a great stimulus for growth, it could give way to other more direct forms of domination. It is worth emphasizing that the most profound changes occurred in the management models as the territory grew. With the increase in resources of all kinds that flowed into Cusco and also the volume of labor force that could be mobilized in the service of the Inca, the power of the curacas linked to the Inca power by reciprocity and by ties of kinship increased. The Inca nobility, which had modified some patterns of reciprocity in the face of the new peoples that were part of the Inca domain, continued to practice this system within their communities. Despite the changes, the common ayllus and the peasants continued with the ancestral system. The ayllus, royal and common, were held together by strong ties of kinship and reciprocity. In practice, everything revolved around the progressive change in the system of control and use of land and water as means of production.

The Inca power made an effort to coherently organize the social and economic relationship of the diverse populations that ended up in its orbit, since it was the only way to achieve sustainable economic and social development in a territory as rugged as the Andes. The Inca society was forged in the integration of a group of heterogeneous populations, each one with its own past and specific form of social and economic organization. This integration responded, on the one hand, to a policy of alliances and pacts based on the exchange of prestige goods and marriages between the ruling elite, but on the other, naturally, in the coercion of a potential military intervention.

When the negotiation did not bear the required results, a determined military action was triggered, followed by a harsh repressive policy. In any case, regardless of the way in which the different ethnic groups entered the orbit of the new state, the Inca power always considered that it could dispose of the economic potential of the territories and the workforce of the subjugated population. Although the difficulty of the Andean geographical environment and the ethnic diversity of its population placed limits on the organizing action of the Incas, the historical documentation allows us to affirm that they always had a precise idea of the ways that should be applied in the organization of the system; or at least that is how they transmitted it to the Spanish chroniclers. Some of the aspects that we have just commented on could mistakenly lead us to an analogy with the proposals of the socialist revolution that were theorized at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century: the Inca state organization that allowed the construction of collective infrastructures that facilitated the increase in cultivation areas in the Andes, the storage of surpluses and the movement through a vast territory of people, goods and services.

In addition, if we take into account the absolute power with which the Inca ruled, the rigid hierarchy of the elite that administered the system, the non-existence of private ownership of the means of production, the absence of a mercantile economy based on money or the discretion with which the collective work of the population was planned, it becomes evident why the Inca model has frequently been presented as a form of primitive communism capable of promoting the planned development of diverse but complementary human groups in an extensive territorial system. However, both the homogeneity of the Tawantinsuo and the structural rigidity of its capital are being questioned, since in essence they do not correspond to or reflect the results of anthropological and ethnohistorical research.

The idealized vision of the Inca culture as a great unit bears little relation to the way in which the different ethnic groups were integrated into the Tawantinsuyu, an integration that responded to very different political strategies, economic patterns and chronological moments. The result would be a flexible and asymmetric socio-economic system in the relationship between its parts, where most of the pre-existing systems were maintained although others, on the other hand, were replaced by models more in line with the Inca ideology. Apparently, the Incas must have incorporated the traditions of the subjugated populations as a strategy of economy of means, since they are cultures that in some cases, such as on the coast, had a millenary history.

We can affirm that the local governors conserved the dominion of their territory and the leadership of their communities, as long as they maintained a receptive attitude to the reciprocity demands that were proposed from Cusco. The traditional Andean system of relations between the elite required the exchange of goods and gifts. The Inca had to show himself “generous” if he wanted them to willingly accept his demands: in particular the control of surpluses and accepting the sending of workers to places sometimes very far away. The Inca expansion was based on an increase in the productive capacity of the territories integrated in the Tawantinsuyo.

For this it was necessary that the aggressive military policy be compensated with a rational management of the work capacities of the populations and in the improvement of the agrarian systems. The chroniclers attribute the technological improvements in the management of the natural environment to the Incas: they would have channeled the rivers, streams and springs to irrigate and drain extensive terraces and thus produce a much more productive agriculture. Archeology has also shown that they experimented with fertilizers, practiced crop rotation, built ridges to exploit floodable lands, acted as botanists in the regeneration and improvement of some species, in short, they knew how to adapt crops to the conditions offered by the different ecological niches. The Incas knew how to take advantage of the complementarity of the ecological floors (vertical archipelago) and strengthen social systems based on productive units (ayllu, ayni and minca) but integrated into a centralized system.

This involved the deployment of a sophisticated storage and redistribution system (roads, dairy farms and colcas), the development of accounting and registration instruments (yupanas and qhipus). Finally, the bureaucracy and the coercive force of the army provided a safer system in the face of the contingencies of the variable climate of the region and the difficulties that could generate alterations in agricultural production and hinder the effective use of the diversity of resources. In summary, the Inca State was only possible from a complex organization of work supported by the reorganization of the territories attributed to the traditional kinship groups (ayllus).

Naturally, this was done by leaving the organization of work and the distribution of subsistence instruments in the hands of local communities. Ultimately, the success of the Inca was based on the expansion of corn cultivation and the construction of terraces and canals. Naturally, this vision cannot ignore the fact that all of this ultimately served so that the dominant group (the Incas by blood and the Incas by privilege) wrested greater production quotas from the different dominated communities; sometimes, it involved the displacement of workers to places far away from their traditional place of residence. The direction and centralized control of the Inca power did not hesitate to apply the harshest measures to optimize the work capacity of the Tawantinsuyo population, first of all, for their own benefit. However, they were also aware that the continuity of the system would only be achieved by guaranteeing that all inhabitants benefited from these advances. The Inca state was the first interested in guaranteeing the redistribution of strategic resources on a large scale. An attitude that we can recognize in the complex system of circulation of goods and people that was the Qhapaq Ñan. Not only was it formed by a network of roads well maintained by the local communities, through which immense herds of llamas circulated transporting all kinds of goods, but it was also equipped with staging establishments (tambos), warehouses (collcas) and large rooms. meeting (kallancas).

As the Inca domain spread throughout the mountain range, we know that large tracts of land and labor force were reserved in the form of mita or yanas to form establishments destined to provide the state system with all kinds of products. The chroniclers comment that the successive rulers “owned” farms cultivated by direct servants, in particular, in the valleys near the capital, scene of the first expansion; this is the case of Tipón, Ollantaytambo or probably Machu Picchu itself.